Article Summary

Introduction

As partisans grow more emotionally hostile toward one another, an important question emerges regarding the determinants of such emotive responses to politics. Previous research shows polarization on policy issues is related to affective polarization, but negative out-party feelings can still emerge despite a lack of ideological polarization. In their paper, Enders and Lupton consider a deeper determinant of emotional responses to politics: value polarization. Their question is simple: does polarization in values beget polarization in emotional evaluations of partisans?

The authors draw on a well-developed literature suggesting Americans hold fairly durable and attitudinally consequential values. Specifically, the values of egalitarianism and moral traditionalism, which exist as opposing poles on a single dimension of values, meaningfully influence attitudes and behavior. Insofar as these values inform more generalized feelings of “good” and “bad,” we should expect them to be related to emotional responses to parties couched in positive and negative affect. The more extreme one’s value position, perhaps the more extreme their evaluations of parties and partisans. Additionally, as elite polarization has worsened over the last several decades, the authors expect the connection between core values and affective judgements to strengthen.

Analytical Approach

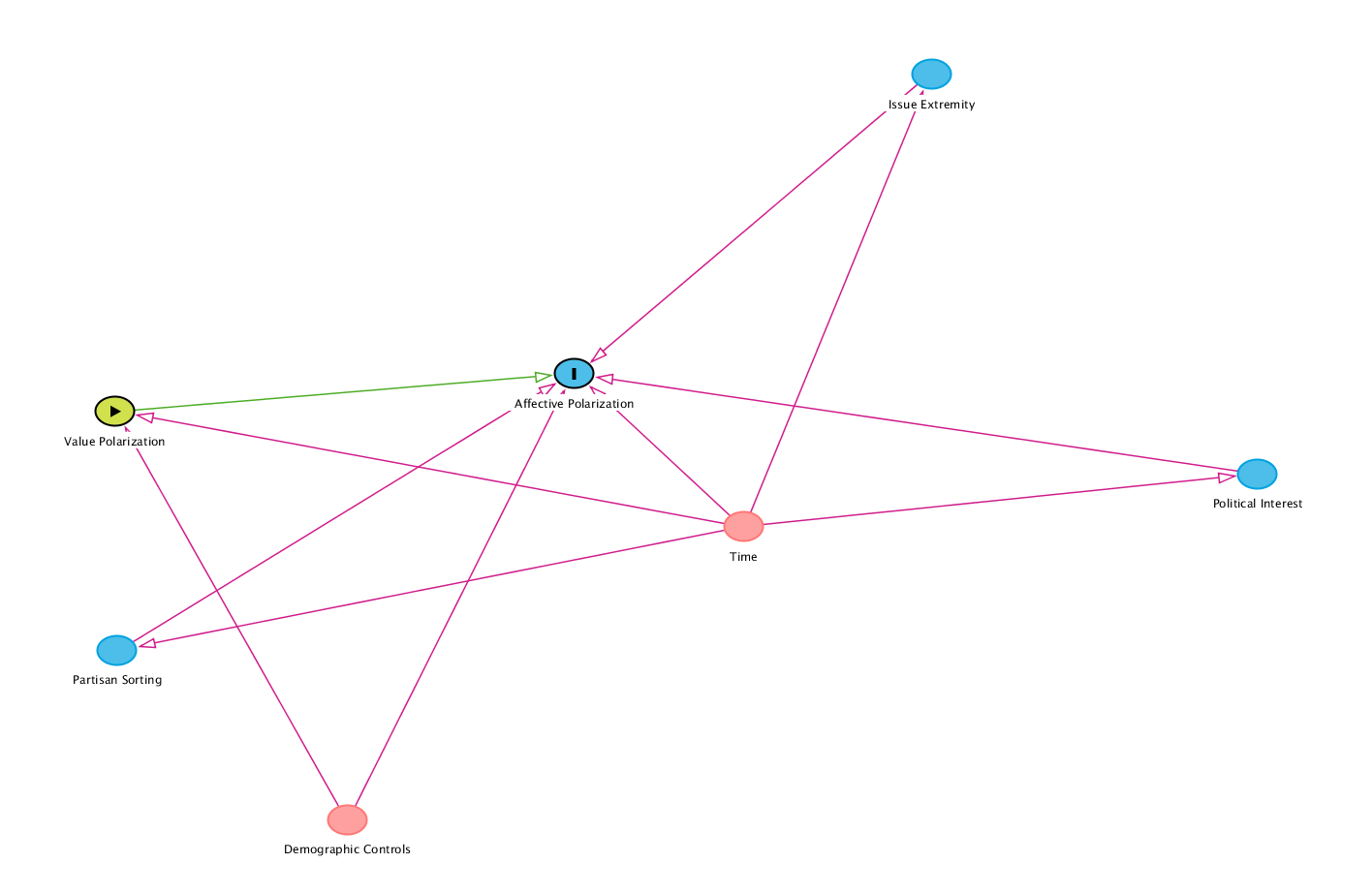

The authors leverage ANES survey data from 1988-2016 in a time-series cross-sectional design. They operationalize their main independent variable, value polarization, by creating an index of preference for egalitarianism versus moral traditionalism and taking the absolute difference of that measure and the mean value orientation of the opposing party by individual. Their main dependent variables are standard affective polarization scores for parties, ideological groups, and presidential candidates (on a 101-point scale). They include controls for issue extremity, partisan sorting, political interest, and demographics, with the inclusion of year fixed-effects in an OLS regression. All variables are scaled 0-1 for comparability. The directed acyclic graph of this design is given in the figure below:

Additionally, the authors concede it is possible their theorized relationship between value polarization and affective polarization goes in the opposite direction: increasingly polarized emotional responses to parties and partisans could cause divergence in values. To rule out this possibility, they utilize ANES panel data from 1992-1996 and implement a cross-lagged panel design, simultaneously estimating the effect of one variable (lagged) on the other and vice-versa with the same sets of lagged controls. This allows for the authors to determine which measure is more strongly related to downstream realizations of the other.

Main Findings

Results from the time-series cross-sectional model show a strong, positive relationship between value polarization and affective polarization. The greater the distance between one’s value orientation and that of the opposing party, the greater the gap in affective evaluations of parties and partisans. This relationship appears to be substantially stronger than that between issue extremity and affective polarization, but not as strong as partisan sorting. Additionally, the marginal effect of value polarization increases dramatically over time.

The cross-lagged panel model corroborates this main result. For both affective feelings toward parties and ideologues, lagged value polarization is a significant predictor, whereas lagged affective feelings are not significant predictors of later value polarization (controlling for all previously mentioned variables). However, neither lagged predictor is significantly associated with later values of the other when using the candidate-specific measure of affective polarization. The authors suggest this is a particularly hard test for their hypothesis, as the lagged periods are on 4-year intervals and candidates (and their associated characteristics) change markedly during such a period of time.

Implications

The results of this paper suggest a strong connection between deeply held values and emotional reactions to politics beyond simple measures of issue polarization. The divides between Republicans and Democrats, then, are not just skin-deep and go beyond simply sorted social identities; animosity is related to deeply held views of what is good and what is bad. There seems to be some non-negligeable “glue,” so to speak, holding attitudes and affect together.

While the authors acknowledge value positions are not immutable, this does raise some concern about the ability to reverse affective polarization. If affect is rooted in deeply held beliefs, how easily can it be alleviated? Enders and Lupton contend there may be more common ground with regard to values than other areas, so perhaps an appeal to common values could provide inroads to a broader population. Reaching more extreme portions of the population, however, may be out of reach.

Questions left unanswered

One question left unanswered by this paper is the direction of the causal arrow between partisan sorting and value polarization. Both were shown to be important factors in affective polarization, but are plausibly linked to one another and not analyzed separately in the cross-lagged panel analysis. Additionally, the role of elite polarization is unclear. While the authors framed the growing importance of values against the backdrop of increasing elite polarization, it does not enter the analyses through anything but the temporal component of the model.

Methods and Analysis

Was the study and its analyses pre-registered?: No

Did the study rely on proxy variables to measure polarization?: No

Were standard p-value thresholds used (p<.05 or 95% Confidence Intervals that don’t overlap zero)?: Yes

- Largest p-value presented as significant: 0.05

Were correlational results interpreted with causal language?: No

Limitations / Weaknesses

The authors analyze the roots of affective polarization through a novel operationalization of value polarization, which provides very interesting insight into facets of political psychology thus far left unconsidered in the affective polarization literature. However, there are a few ambiguities with the measure that the paper would benefit from alleviating. First, the operationalization of value polarization is agnostic with regard to the end of the one-dimensional scale the respondent is on. For measures of affective polarization, this is typically a non-issue, as respondents almost invariably rate their own party more warmly than the other, so the direction of the affective difference is implied. The partisan distribution of values, however, is much less polarized according to figures in the appendix. It is possible (certain, even) for Democratic respondents to lean further toward the moral traditionalism end of the spectrum than the mean Republican, meaning the value polarization measure is actually an indicator of distance from their own party. This makes some of the findings of the paper slightly more difficult to interpret. Second, the authors frequently refer to these values as being “deeply held.” But is that necessarily the case? There does not appear to be any independent analysis suggesting consideration of these values trumps others in decision-making, so it is possible such values are held with fairly low intensity. An auxiliary analysis testing such intensity would be useful to understand how values function in attitude formation and decision-making.

Open Data & Analyses

Does the article make the replication data publicly available?: Yes

Does the article make the replication analysis scripts publicly available?: Yes

Article Citation

Enders, A., & Lupton, R. (2021). Value extremity contributes to affective polarization in the US. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(4), 857-866. doi:10.1017/psrm.2020.27

Bibtex

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

@article{enders_lupton_2021,

title={Value extremity contributes to affective polarization in the US},

volume={9},

DOI={10.1017/psrm.2020.27},

number={4},

journal={Political Science Research and Methods},

publisher={Cambridge University Press},

author={Enders, Adam M. and Lupton, Robert N.},

year={2021},

pages={857–866}

}