Article Summary

Introduction

A large literature documents increasing partisan polarization in the American public across a variety of characteristics. Namely, partisans are polarized in both their affective evaluations of the other party and their perceptions of who those out-party members are. It is unclear, however, which judgment causes the other, and the two phenomena have largely been studied in isolation.

In their paper, Armaly and Enders ask what the causal relationship is between affective polarization and perceptions of polarization. They contend affective polarization likely precedes perceptions of polarization, as social identification generally precedes “downstream” evaluations of politics. While it is true that skewed perceptions can generate negative emotions, they argue one’s emotional attachment to party is more broadly consistent with a generalized, ideological worldview that ought to precede perceptions of polarization.

Answers to the authors’ question may provide hints as to the underlying nature of affective polarization being either predominantly ideological or rooted in group identity, as they may be conditioned on other factors such as political sophistication. The authors theorize affective polarization is largely ideological, so the relationship between affective polarization and perceived polarization ought to be strongest in the most politically sophisticated respondents.

Analytical Approach

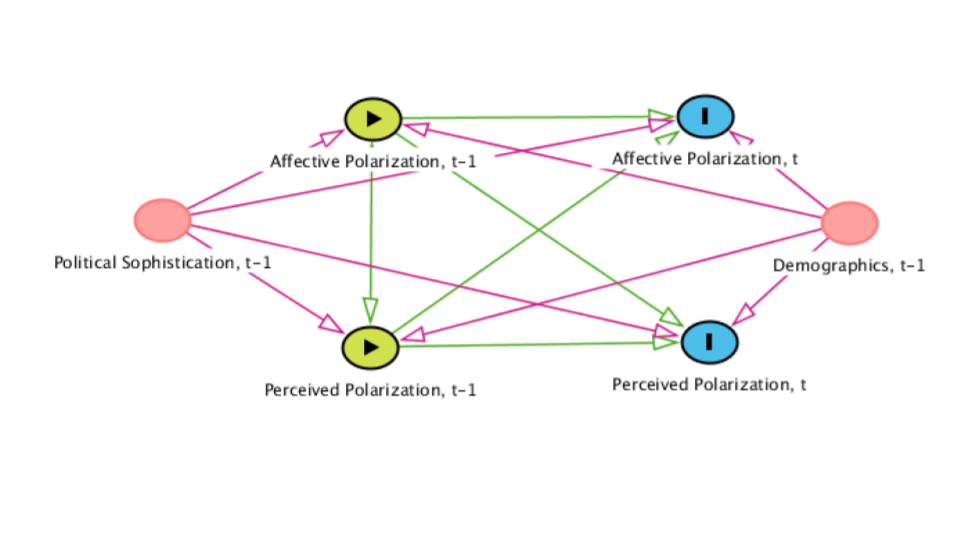

The authors use panel data from the 1992-1996 and 2008-2009 ANES waves, measuring affective polarization and perceived polarization across both waves with feeling thermometers and policy ratings of parties. The authors then implement a cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) to estimate the effects of lagged values of affective and perceived polarization on contemporary values. This hypothetically allows for the estimation of a causal effect of one value on the other, as the authors are controlling for previous values in each dependent variable. The full DAG is given below:

If one cross-lagged effect appears stronger than the other, that would provide evidence of such an effect preceding the other causally. The authors control for a series of demographic variables measured at t-1, as well as the level of political sophistication. Because they believe political sophistication should moderate the cross-lagged effects, the authors run the same models, but stratified on terciles of political sophistication. If their hypothesis is correct, the relationship between cross-lagged effects should be strongest at higher levels of political sophistication.

Main Findings

First, using non-panel data from the cumulative ANES file from 1972-2016, the authors show a strong upward trend in perceived polarization among the most affectively polarized, but no such trend in affective polarization among those with the most perceived polarization, suggesting affective polarization likely precedes perceived polarization.

Turning to the causal analysis, the authors find past affective polarization predicts future perceived polarization, but not vice-versa. While both measures show stability from wave to wave, only affective polarization has a cross-lagged effect on perceived polarization.

The authors then consider the moderating effect of political sophistication. For those scoring low on political information, neither lagged affective or perceived polarization has an effect on future values of the other variable. However, for respondents with middling or high levels of political information, lagged affective polarization predicts future perceived polarization, but not vice-versa. Again, the variable measures appear stable over time, but only for the middle and high information groups.

Implications

The results suggest the causal arrow goes from affective polarization to perceived polarization, not the other way around. More generally, however, they suggest manifestations of polarization are plausibly connected by similar psychological roots, allowing for a more holistic evaluation of polarization in today’s politics. Specifically, the authors argue their results are consistent with a more ideological understanding of affective polarization, as only more politically sophisticated individuals demonstrated a connection between affective and perceived polarization.

From an interventions perspective, the results also suggest perception-correcting interventions may not be treating the root cause of polarized perceptions, which may lie in affective polarization. While such interventions may prevent some degree of perceptions feeding a self-fulfilling prophecy of polarization, affective polarization comes prior to polarized perceptions.

Questions left unanswered

The authors begin the paper with a simple question about the direction of the causal relationship between affective and perceived polarization, and attempt to get such causal estimates with their approach. Their answer, however, leads to more questions about the nature of affective polarization. The authors suggest ideological polarization may underlie affective polarization most primally, due to the results around political sophistication. This is not tested in the paper, but future work could more carefully consider the causal effects of policy versus social polarization on perceived polarization. Furthermore, it could be the case that the causal arrow is different for each manifestation of affective polarization; social polarization may beget perceived polarization, but ideological polarization may be a product of perceived polarization (for example).

Methods and Analysis

Was the study and its analyses pre-registered?: No

Did the study rely on proxy variables to measure polarization?: Yes

For the 1992-96 waves, the 100-point thermometer was used, but values all ended in 0, so implicitly it is just an 11-point scale. In the 2008-09 waves, affective polarization was measured using a 7-point scale.

Were standard p-value thresholds used (p<.05 or 95% Confidence Intervals that don’t overlap zero)?: Yes

- Largest p-value presented as significant: 0.05

Were correlational results interpreted with causal language?: No

Limitations / Weaknesses

A growing literature in social psychology has questioned the ability of cross-lagged panel models to uncover causal effects. Specifically, Hamaker et al. (2015) and Lucas (2023) claim such models produce biased and/or spurious estimates of cross-lagged effects in the presence of correlated stable traits. One could imagine observed levels of affective and perceived polarization at both t and t-1 are manifestations of latent traits, which are stably correlated across time but do not causally interact. In fact, the authors show how this could be the case with political sophistication, a latent trait correlated with both affective and perceived polarization. Modeling advances exist to remedy such issues, and could be applied here. Such models also suffer from issues of synchronicity, i.e. measurements occurring at the exact same time. If questions of affective polarization always precede questions of perceived polarization in a survey (in both waves), it is possible such questions prime respondents on their subsequent answers. It is unclear from the paper whether this is an issue for the ANES.

Open Data & Analyses

Does the article make the replication data publicly available?: Yes

Does the article make the replication analysis scripts publicly available?: Yes

Article Citation

Armaly, M., & Enders, A. (2021). The role of affective orientations in promoting perceived polarization. Political Science Research and Methods, 9(3), 615-626.

Bibtex

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

@article{armaly_enders_2021,

title={The role of affective orientations in promoting perceived polarization},

volume={9},

DOI={10.1017/psrm.2020.24},

number={3},

journal={Political Science Research and Methods},

publisher={Cambridge University Press},

author={Armaly, Miles T. and Enders, Adam M.},

year={2021},

pages={615–626}

}