Article Summary

Introduction

This article studies the origins of affective polarization between pairs of parties from a comparative perspective. The authors pose two related questions: Which partisans dislike which opposing parties, and what explains variations in affective evaluations between pairs of parties? These questions are particularly relevant for multi-party systems that, unlike the United States, feature more than two political parties. In such multi-party systems, partisan animosities could occur between various combinations of parties. For instance, partisans could have benign feelings toward most parties but strong negative feelings toward one single party, while others feel negative toward all out-party supporters. To test this, the authors ask respondents to evaluate pairs of parties.

The authors address this question by providing evidence from a cross-national survey and demonstrate that affective polarization is correlated with a number of party-level variables, such as economic and cultural policy disagreements among parties. By offering these insights, the authors contribute to identifying party features that are linked to different levels of partisan animosities between parties across democracies.

Analytical Approach

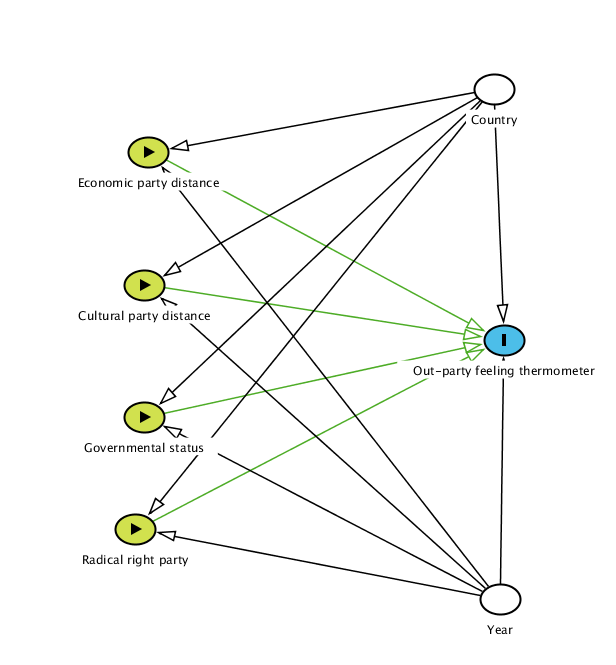

The authors aim to elucidate varying levels of partisan animosities by focusing on dyads of parties. In line with previous research, the authors concentrate on survey participants who self-identify as supporters of a political party. The study’s outcome variable is the responses to the feeling thermometer for all out-parties in a given party system. The authors aggregate these out-partisan responses by calculating the mean for each in-party/out-party dyad and provide additional analyses for individual-level dyads as a robustness test. To explain the different levels of out-party evaluations, the authors consider several variables that might be linked to these variations:

- Greater elite ideological distance, both on the economic and cultural dimensions, leads to higher affective polarization among supporters of these parties.

- Over time, the association between cultural ideological distance and affective polarization between parties has become stronger than the association between economic ideological distance and affective polarization.

- Supporters of parties that form a coalition are less affectively polarized toward out-party coalition party followers.

- Supporters of opposition parties are less affectively polarized toward other out-party opposition party supporters.

- Supporters of radical right parties are more affectively polarized toward out-party supporters than ideological differences and coalition arrangements would predict.

- Supporters of non-radical right parties are more affectively polarized toward radical right party supporters than ideological differences and coalition arrangements would predict. These expected associations are visualized in the figure below. In addition to the several variables expected to predict out-party feelings, the authors include controls for each country and survey wave.

The authors utilize data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES), totaling 2,232 pairs of political parties in 20 Western democracies. To determine the ideological distance between party pairs, the authors rely on the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP), which derives party scores for their ideological stances from campaign manifestos.

Main Findings

The authors find empirical support for most of their theoretical expectations: Supporters of political parties are more polarized when their parties are more ideologically distant from each other, both on the economic and cultural dimension. However, contra theoretical expectations, there has not been a substantial relative increase in the association of cultural over economic policy distance and affective polarization over time. Moreover, supporters of opposition parties feel more positively about other opposition parties, and supporters of a coalition party feel more positive about other coalition parties. Lastly, radical right party supporters show stronger animosity toward out-parties than their ideological distance and their governmental status would predict, and vice versa.

Implications

The authors highlight two key implications of their study. Firstly, they note that the animosity between supporters of radical right parties and other parties extends beyond mere policy disagreements. This insight is significant because it underscores that policy differences do not always equate to affective polarization. The hostile rhetoric of mainstream political leaders toward radical right parties aligns with the intense partisan animosities observed between radical right party supporters and out-parties in many Western democracies.

Secondly, the authors conclude that power-sharing arrangements can help mitigate affective polarization. Their findings indicate that coalition governments reduce the animosity between their supporters, suggesting that sharing governmental power can alleviate negative partisan sentiments that may arise from policy disagreements among governing parties. The authors suggest that multi-party systems, where power-sharing in coalition governments is necessary, may experience less partisan polarization compared to majoritarian systems like that of the United States.

Questions left unanswered

The authors acknowledge a limitation in their study: it cannot precisely determine the mechanisms through which their party variables are linked to partisan animosities. For example, how exactly do supporters of a coalition government become more positive in their feelings toward supporters of other parties in the government? Is it because their party leaders speak more positively about each other when they are in government, or is it because supporters of coalition parties approve of the policies implemented by the government and attribute this to all parties involved in the government? The authors also suggest using panel data to examine how supporters of a party react when that party enters or exits a coalition government.

Methods and Analysis

Was the study and its analyses pre-registered?: No

Did the study rely on proxy variables to measure polarization?: Yes

Like-dislike scale for political parties (and not their supporters) was used; response scale ranges from 0-10 (and not from 0-100)

Were standard p-value thresholds used (p<.05 or 95% Confidence Intervals that don’t overlap zero)?: Yes

- Largest p-value presented as significant: 0.05

Were correlational results interpreted with causal language?: No

Limitations / Weaknesses

The authors are transparent about the correlational nature of their results. However, the article does not directly address the systematic differences associated with the existence of coalition versus single-party governments. Countries with a single-party government in the executive branch, such as the United States, are not only different from countries that are governed by multi-party governments, such as Sweden or Germany, with respect to the composition of government but also how institutions are designed more generally and how the party system has evolved over time. Certainly, the result that supporters of government parties feel more positively about each other yields face value, but democracies with coalition governments usually feature a party system with a higher number of parties, and partisan animosities toward government vs. opposition parties could be similarly strong as partisan divides between the two principal parties in single-party governments, such as in the United States. Hence, taking the broader institutional background into account may be in order when comparing the effect of power-sharing on varying levels of partisan animosities across countries.

Open Data & Analyses

Does the article make the replication data publicly available?: Yes

Does the article make the replication analysis scripts publicly available?: Yes

Article Citation

Gidron, N., Adams, J., & Horne, W. (2023). Who Dislikes Whom? Affective Polarization between Pairs of Parties in Western Democracies. British Journal of Political Science, 53(3), 997–1015.

Bibtex

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

@article{gidron2023dislikes,

title={Who dislikes whom? Affective polarization between pairs of parties in western democracies},

author={Gidron, Noam and Adams, James and Horne, Will},

journal={British Journal of Political Science},

volume={53},

number={3},

pages={997--1015},

year={2023},

publisher={Cambridge University Press}

}