Article Summary

Introduction

This article contributes to the debate on the extent to which American voters have become increasingly polarized and, if so, whether polarization manifests in increasingly extreme policy preferences or political attitudes. The article thus asks: How has polarization developed over time? Is polarization mainly driven by disagreement over policy preferences or more deep-seated partisan identities?

Mason argues that the increasing alignment between partisan and ideological identities has exacerbated partisan bias and negative evaluations and feelings toward the out-party. This is because this alignment has solidified a social identity that, in turn, induces more positive attitudes toward the in-party vis-à-vis the out-party. Hence, the author expects that the increasing sorting of partisan and ideological identities is associated with growing negative sentiments toward the out-party.

Analytical Approach

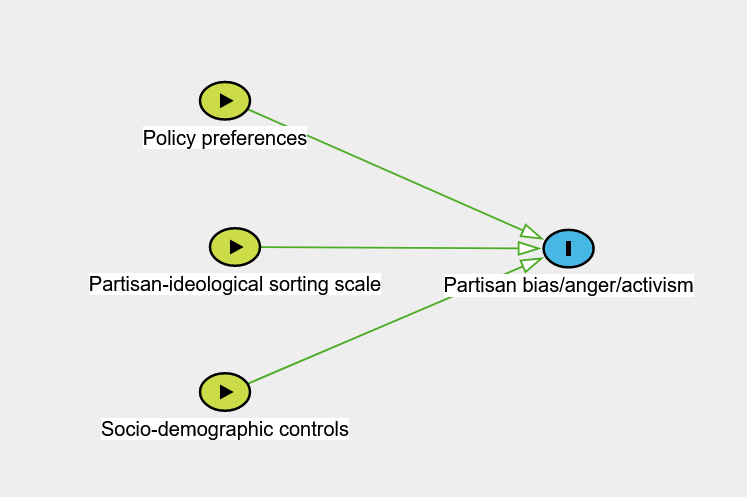

The author relies on a partisan-ideological sorting scale to measure their key independent variable. This scale subtracts the strength of party identity from the strength of ideology identity, where higher values indicate more alignment between Democratic and liberal orientations or Republican and conservative orientations. The author selects a number of outcome variables aimed at measuring party bias, activism, and anger. Specifically, the author measures out-party bias by subtracting the out-party from the in-party thermometer. Furthermore, they include an item asking about anger toward the out-party’s presidential candidate and political activism and control for policy preferences and sociodemographic variables. The data source is the American National Election Study (ANES) from 1972 to 2004, complemented with an ANES panel from 1992 to 1996. The figure below illustrates the causal model developed in the analysis.

Main Findings

The author finds support for the hypothesis that ideological and partisan sorting are associated with stronger partisan bias, party activism, and anger. The panel data furthermore indicates that for voters with increasing partisan sorting, partisan bias, party activism, and anger subsequently increase.

Implications

Based on the finding that ideological and partisan sorting is associated with partisan bias, party activism, and anger, the author concludes that even when voters agree on policy issues, they may still dislike each other due to in-group versus out-group bias. This result suggests that the American public is driven more by a sense of “team spirit” than by a “logical connection” between policy preferences and political behavior. Perhaps paradoxically, this could lead to a situation where the public agrees on many policy issues but is nevertheless divided into two camps that harbor mutual dislike.

Questions left unanswered

A question unaddressed by the author concerns the origins of increased ideological and partisan sorting. Why do citizens become increasingly sorted in their ideological and party identities? While not exhaustive, shifts in the ideological composition of the Democratic and Republican parties could have induced similar sorting among voters. Furthermore, increased political interest and knowledge in the public could have led to a process in which partisan identities have become more aligned to increase consistency between group identities.

Methods and Analysis

Was the study and its analyses pre-registered?: Study was conducted before 2015

Did the study rely on proxy variables to measure polarization?: No

Were standard p-value thresholds used (p<.05 or 95% Confidence Intervals that don’t overlap zero)?: Yes

- Largest p-value presented as significant: 0.05

Were correlational results interpreted with causal language?: Yes

Example statement: “In the first column of Table 1, the effect of sorting on thermometer bias is large and significant.” (p. 134)

Limitations / Weaknesses

To complement the cross-sectional ANES analysis, Mason presents evidence from an ANES panel collected between 1992 and 1996. However, due to the relatively small sample size and the fact that not all questions were asked to respondents, the author was left with around 100 observations to study whether changes in partisan and ideological sorting are associated with subsequent partisan bias and other outcomes. This small sample size raises questions, and it remains unaddressed to what extent panel attrition, i.e., respondents with a certain sociodemographic profile dropping out of the survey in the second wave, biases the results of the analysis.

Open Data & Analyses

Does the article make the replication data publicly available?: Yes

Does the article make the replication analysis scripts publicly available?: Yes

Article Citation

Mason, L. (2015). “I Disrespectfully Agree”: The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145.

Bibtex

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

@article{Mason.2015,

author = {Mason, Lilliana},

year = {2015},

title = {``I Disrespectfully Agree'': The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization},

pages = {128--145},

volume = {59},

number = {1},

journal = {American Journal of Political Science}

}