Article Summary

Introduction

Many voters express a strong dislike for the political party they oppose. But when in life does this animosity emerge? Do even children harbor politically polarized attitudes? These are critical questions to ask as we seek to understand how and why strong partisan feelings occur and devise interventions to ameliorate partisan animosity.

Past research has indicated otherwise, showing that kids hold political leaders of both parties in relatively high esteem. However, that research was conducted in the 1960s and 1970s — long before the dramatic rise in US polarization. In this short American Political Science Review letter, Tyler and Iyengar (2023) update our understanding of young people’s partisan attitudes by investigating whether the gap in adults’ and adolescents’ levels of polarization has narrowed over the past 40 years.

Analytical Approach

The authors examine separate samples of adolescents (and their parents) surveyed in 1980 and 2019. The 1980 data come from a telephone survey of Wisconsin families, while the 2019 subjects were recruited from YouGov’s online panel.

Both surveys measure party ID and partisan trust, which Tyler and Iyengar use as a proxy for affective polarization. Specifically, they use the following question, asked of both parties: “How often do you think you can trust [the Democratic/Republican Party] to do what is right?” With these 5-point items, they measure the level of trust respondents express for their party (in-party trust), their level of trust in the opposite party (out-party trust), and the difference between these values (partisan trust polarization). To validate this proxy measure, the authors use the 2019 survey to demonstrate that partisan trust and partisan feeling thermometer ratings are strongly related.

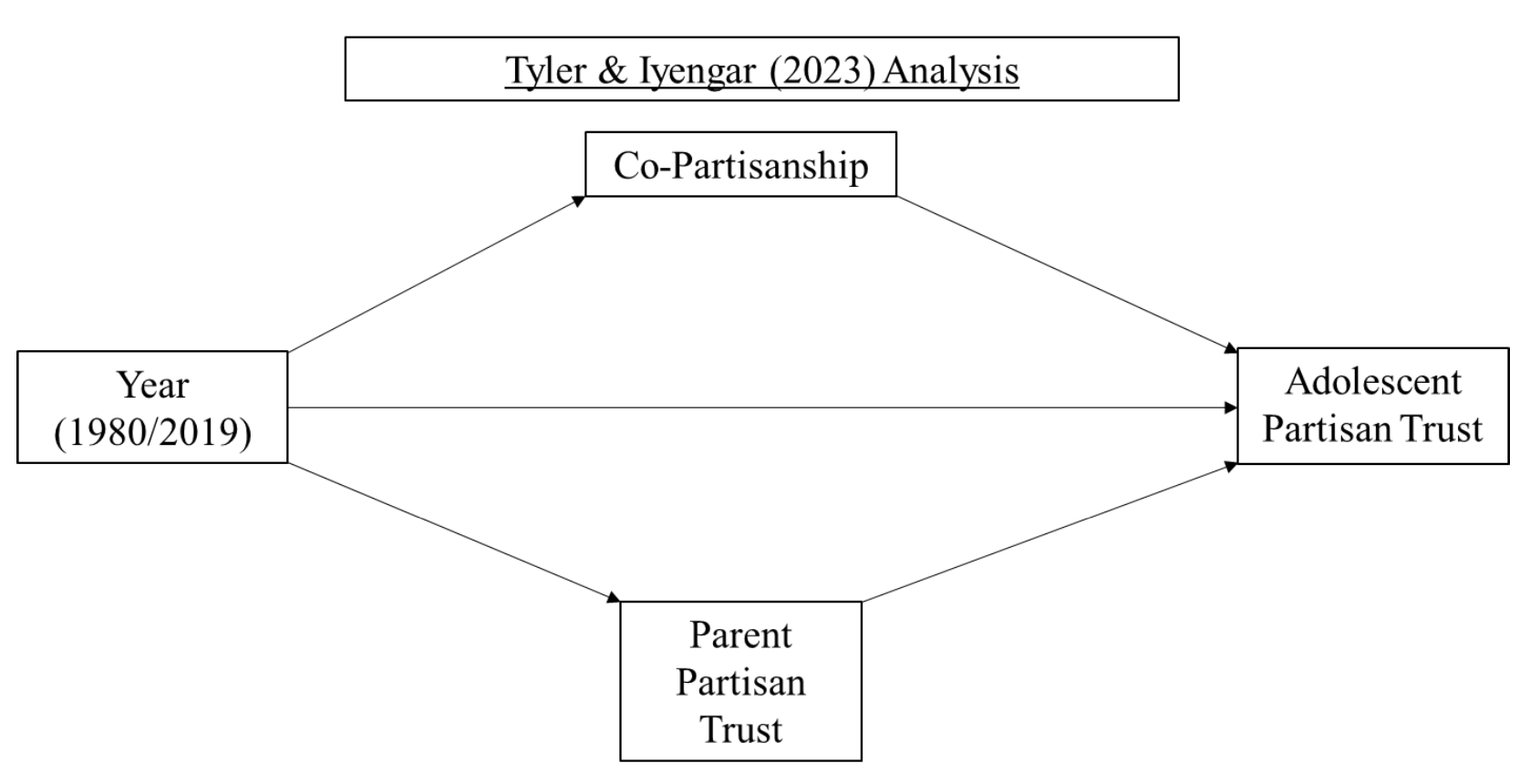

With these measures, Tyler and Iyengar compare levels of partisan trust among adolescents and adults in both 1980 and 2019. They also gauge how strong of a relationship exists between partisan trust and whether the parent and child identify with the same political party (which they refer to as “child-parent co-partisanship”).

Main Findings

In both 1980 and 2019, almost as many adolescents as adults identified with a political party: roughly three-quarters of the sample. So in terms of simple party identification, little appears to have changed since 1980.

By contrast, the gap in partisan trust levels has narrowed dramatically. Adolescents in 1980 trusted both parties much more than their parents, whereas 2019 adolescents reported trust levels that were barely distinguishable from adults. So while adolescents today are no more likely to identify with a political party compared to 1980, they are now noticeably less trusting of the parties.

Tyler and Iyengar then turn to polarization in partisan trust. For both adults and adolescents, their findings are consistent with past literature: Subjects in 2019 expressed much more negative feelings toward the out-party than in 1980. Even the youngest adolescents in the 2019 sample exhibit the same levels of out-party distrust as adults, indicating that current levels of affective polarization are already reflected in kids by the time they turn 11.

Lastly, the authors provide three separate pieces of evidence that suggest — but do not prove — parents are the main driver of adolescent polarization. First, they show large increases in parent-offspring partisan alignment, with the percentage of parent-child pairs who identify with the same party increasing from 56% to 81%. Second, they establish that child-parent co-partisanship is associated with significantly higher polarization of party trust among adolescents in 2019, whereas adolescents with an out-party parent are no more polarized in 2019 than in 1980. Finally, they demonstrate how parents’ levels of affective polarization are much better predictors of their children’s polarization levels in 2019, with the relationship roughly tripling in strength since 1980. All of these results are consistent with the theory that adolescents acquire their polarized attitudes from their parents.

Implications/Unanswered Questions

Children in the 1960s and 1970s held political leaders of both parties in high regard. This article suggests that this civic idealism has receded. Affective polarization now begins early, with even 11-year-olds exhibiting roughly the same levels of in-group favoritism and out-group distrust as adults. Today, children tend to mirror their parents’ political animus right along with their party ID.

These findings raise a few questions for future research. First, the youngest subjects in the 2019 sample — 11-year-olds — already have stable partisan identification and match their parent’s level of out-party distrust. So how young are children nowadays when they first develop political identities? And when do they become affectively polarized?

Second, are parents truly the main driver of their kids’ political development? That’s how the authors (cautiously) interpret their results, and this explanation is consistent with the broader political socialization literature. But more work needs to be done on this question. As Tyler and Iyengar concede, these results may instead be a result of children’s broader social environments. Politically polarized parents may live in more politically congenial areas, which may in turn polarize their children against the other party.

Finally, to what extent are healthy civic attitudes still developing in upcoming, more politically polarized generations? Researchers in the past have considered political socialization in childhood to be critical for developing an appreciation of democratic norms and institutions in future citizens. How strongly are adolescents’ lower levels of partisan trust associated with a decline in respect for democratic norms?

Methods and Analysis

Was the study and its analyses pre-registered?: No

Did the study rely on proxy variables to measure polarization?: Yes

In both the 1980 and 2019 surveys, the authors employ measures of party trust as a proxy for affective polarization. Specifically, they ask, “How often do you think you can trust [the Democratic/Republican Party] to do what is right?” The 2019 survey also employs standard feeling thermometer measures of both parties, which the authors use to validate the trust measure as a proxy for polarization by showing a strong relationship between partisan trust and partisan warmth.

Were standard p-value thresholds used (p<.05 or 95% Confidence Intervals that don’t overlap zero)?: Yes

- Largest p-value presented as significant: 0.05

Were correlational results interpreted with causal language?: No

Limitations / Weaknesses

This paper provides a valuable snapshot of adolescents 40 years ago compared to today, but it has a few limitations. First, outside of party identification, the authors do not look at any other areas where parents and children may agree or disagree. For instance, it may be fruitful to gauge how much adolescents agree with their parents on various policy issues, as opposed to just whether they share a symbolic attachment to a political party. Second, the survey sizes (319 in 1980, 500 in 2019) occasionally make it impossible to compare certain groups in the sample with any precision. Most notably, when the authors contrast the levels of partisan trust polarization among children with out-party parents, only 24 adolescents in the 2019 sample fit into this category. This is likely too small of a sample to provide a clear, comparable estimate. As a result, we should not discount the possibility that adolescents who disagree with their parents’ party identification are not as polarized as similar adolescents in 1980. This would undermine the authors’ theory that parental polarization drives adolescent polarization. Third, the authors do their best to account for other things that could influence adolescents’ levels of polarization, such as their peers and their online exposure to politics. As they outline in the paper’s appendix, they find no significant relationships. However, they are only able to use self-reported measures of how much subjects a) discuss politics with their friends and b) follow politics online. These measures, like many self-report measures, are far from fully reliable. So the fact that the authors find no impact for them does not necessarily mean that peer groups and online politics have no polarizing effects on young people’s political attitudes.

Open Data & Analyses

Does the article make the replication data publicly available?: Yes

Does the article make the replication analysis scripts publicly available?: Yes

Article Citation

Tyler, M., & Iyengar, S. (2023). Learning to Dislike Your Opponents: Political Socialization in the Era of Polarization. American Political Science Review, 117(1), 347-354. doi:10.1017/S000305542200048X

Bibtex

1

@article{tyler_iyengar_2023, title={Learning to Dislike Your Opponents: Political Socialization in the Era of Polarization}, volume={117}, DOI={10.1017/S000305542200048X}, number={1}, journal={American Political Science Review}, publisher={Cambridge University Press}, author={Tyler, Matthew and Iyengar, Shanto}, year={2023}, pages={347–354}}