Article Summary

Introduction

Concerns about increasing partisan animosity aren’t limited to just the U.S. Across several Western democracies, hostilities between members of opposing parties have risen. Several scholars have investigated features of these democracies that may lend themselves to more or less affective polarization, but one understudied component is the politicians themselves. That is, does it matter who holds office with regard to partisan animosity?

In their paper, Adams et al pull upon research on gender and politics to delve into this question. Previous scholars have noted women members of parliament (MPs) disproportionately display more favorable lawmaking and representative qualities compared to their male counterparts. Women MPs tend to be more consensual, less adversarial, and less negative in their leadership styles, which may reflect “gendered socialization processes or women’s strategic efforts to overcome marginalization within political institutions.” Citizens and journalists view women MPs consistent with many gender-trait stereotypes as being more compassionate and caring and voice preferences for institutions with greater female representation.

As such, the authors of this paper contend citizens may display more positive affect toward rival parties with greater proportions of women MPs. Such a finding holds implications for descriptive representation, as parties may feel incentives to recruit more women lawmaking candidates for the parliamentary delegations as a means to reduce affective polarization and appeal to a broader base of voters.

Analytical Approach

The authors combine data on women’s membership in parliamentary delegations in 20 Western democracies with survey data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) spanning 1996 to 2017. For each country, survey respondents complete 0-10 feeling thermometers of all parties active in the country. The authors average these thermometer ratings for each of the 1,842 directed party dyads in the data. For example, if the data included 3 parties, A, B, and C, there would be 6 party dyads (each party’s evaluation of the other two).

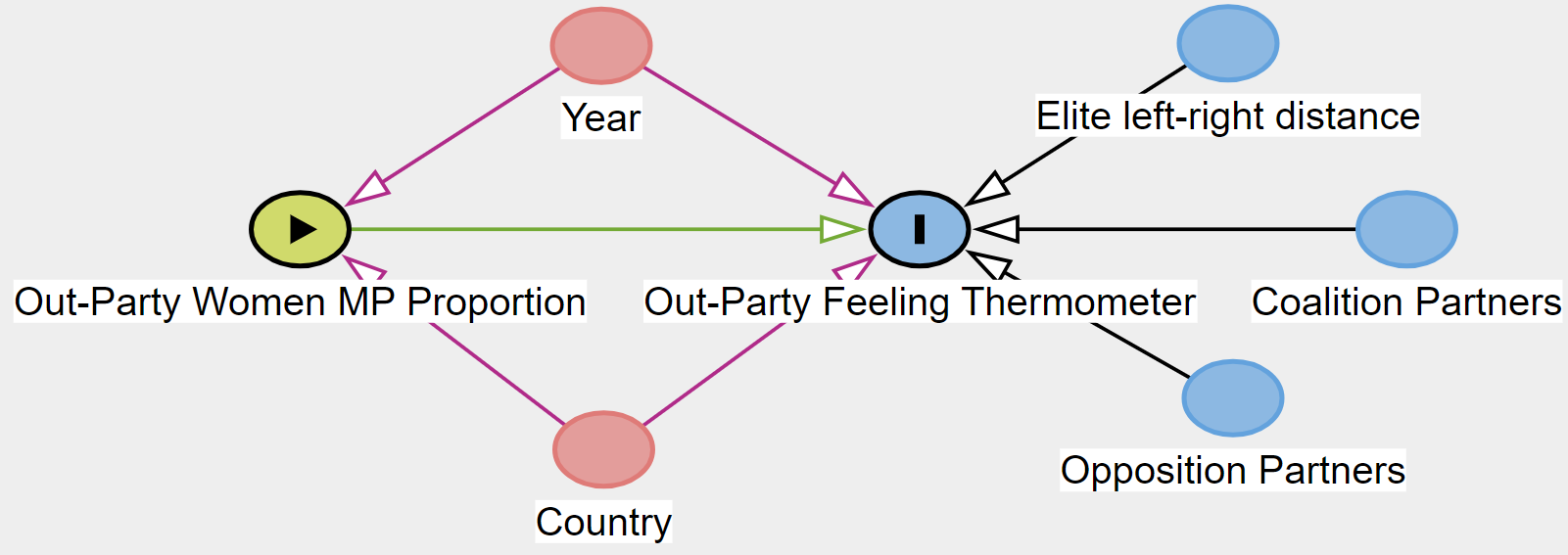

For the main analysis, the authors regress the out-party affect measure for party j at time t on the proportion of women MPs in party j at time t-1. They control for ideological distance between parties and whether the parties in the dyad are coalition partners or opposition partners, which may influence baseline affective evaluations. The authors include year and country fixed effects, meaning the estimates are calculated within-country and within-election. The model can be visualized in the figure below:

Figure 1: DAG of Adams et al. (2023) Main Analysis

If greater proportions of women in parliamentary delegations decreases affective polarization, we should expect to see a positive and significant coefficient for the main independent variable.

Main Findings

Consistent with their hypothesis, the authors find greater levels of women’s descriptive representation in parties’ parliamentary delegations is associated with warmer feelings toward such parties. A one standard deviation increase in the proportion of women MPs (13% to 45%) increases feeling thermometer rates by 0.55 (one third of a standard deviation of the dependent variable, scaled 0-10). This finding persists with the inclusion of control variables for elite left-right ideological distance and whether the party dyad includes coalition or opposition partners (all of which have coefficient signs in the expected direction and are statistically significant).

The authors conduct a number of robustness checks to corroborate their main result. They split their sample to male and female respondents only and also subset to later years in the data to focus on more modern campaigning environments. The results persist in both cases, as well as in different model specifications using alternative standard error clustering, individual-level units of analysis, and alternative country and year fixed effects.

Extending their findings, the authors consider whether there may be diminishing marginal returns in the affective bonus enjoyed by high-women MP proportion parties when the proportion exceeds 50% (ie, is beyond parity in the population). They add a squared term for women MP proportion to their model, and find it to be statistically significant and negative, implying that at the highest levels of women’s descriptive representation, parties begin to experience affective penalties from out-partisans. The authors also find the affective bonus of women MPs is greater in parties led by men.

Implications

The study has implications for both affective polarization and descriptive representation of women in Western democracies. While many comparative studies have focused on more permanent features of electoral systems (such as proportionality), the composition of parliamentary delegations is somewhat more malleable and offers potential inroads against affective polarization.

Furthermore, the study implies benefits of women’s descriptive representation beyond increasing feelings of institutional trust. Having greater proportions of women MPs may help to bridge affective divides between parties, even when the ideological distance between them is large.

However, the study raises questions on how parties may leverage women’s descriptive representation to achieve their electoral ambitions. While an optimistic appraisal may hope parties genuinely try to ameliorate feelings of partisan animosity and increase parity through the recruitment of more women candidates, a more pessimistic view may be that parties artificially increase their gender parity as a means to justify more antidemocratic policies.

Questions left unanswered

While the authors determine there is a relationship between women’s descriptive representation and out-party affect, they do not directly test affective polarization as the dependent variable. So while we have a potential answer to the question of whether the proportion of women MPs is correlated with warmer feelings of opposition parties, we do not know if it reduces affective polarization, as the authors only utilize one of the component measures. Of course, this is likely to be supported by the data, and can be easily done with the replication materials.

Methods and Analysis

Was the study and its analyses pre-registered?: No

Did the study rely on proxy variables to measure polarization?: Yes

Instead of 0-100 thermometer, 0-10 used

Were standard p-value thresholds used (p<.05 or 95% Confidence Intervals that don’t overlap zero)?: Yes

- Largest p-value presented as significant: 0.05

Were correlational results interpreted with causal language?: No

Limitations / Weaknesses

The authors in no way claim to be presenting a causal relationship between women’s descriptive representation and feelings of out-party antipathy. However, more could be done to evaluate whether the mechanism behind the relationship is truly due to gender, or to associated features of the party. It seems unlikely survey respondents know the gender compositions of party parliamentary delegations or have it top of mind when evaluating parties. It is possible, however, that respondents subconsciously associate greater consensual lawmaking to parties with more women MPs, but the research cited in the paper only shows voters associate such gender-trait stereotypes with individual MPs. A number of mechanism checks of this sort would greatly bolster the main result. Furthermore, it is unclear how the control variables added to the regression would confound the relationship between proportion of women MPs and feelings of out-party warmth. Certainly they change the baseline level of warmth, but there are many other variables that plausibly confound the main relationship of interest. Party nomination systems or party support for particular issues related to gender may plausibly be related to both the proportion of women MPs and feelings of warmth. While an experimental manipulation may be outside the realm of possibility, something similar in a survey experiment setting randomizing the number of women MPs with an assortment of other factors may provide more causal leverage.

Open Data & Analyses

Does the article make the replication data publicly available?: Yes

Does the article make the replication analysis scripts publicly available?: Yes

Article Citation

Adams, J., Bracken, D., Gidron, N., Horne, W., O’Brien, D., & Senk, K. (2023). Can’t We All Just Get Along? How Women MPs Can Ameliorate Affective Polarization in Western Publics. American Political Science Review, 117(1), 318-324. doi:10.1017/S0003055422000491

Bibtex

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

@article{adams_bracken_gidron_horne_o’brien_senk_2023,

title={Can’t We All Just Get Along? How Women MPs Can Ameliorate Affective Polarization in Western Publics},

volume={117},

DOI={10.1017/S0003055422000491},

number={1},

journal={American Political Science Review},

publisher={Cambridge University Press},

author={Adams, James and Bracken, David and Gidron, Noam and Horne, Will and O’Brien, Diana Z. and Senk, Kaitlin},

year={2023},

pages={318–324}

}